Massenet’s Cendrillon premieres at the Met

Massenet’s Cendrillon, which made its Metropolitan Opera premiere last week, is an enchantingly lovely opera, full of the delicate magic of a fairy tale. Laurent Pelly’s production (he also designs the costumes) is both understated and over the top: the grays, drab greens and shadows augment Cendrillon’s introversion, loneliness, and misery…it’s how more or less the world looks and sounds when you’re down, so I’m told…in contrast to the brilliant reds, purples, and other bright colors ramping up the nervous extraversion of the shallow courtiers, all of this intersected at various times with the nervous scurry of servants and family, primarily Cendrillon’s horrid dragon stepmother Madame de la Haltière and her two flaky daughters Noémie and Dorothée. At two points in the evening it seems the entire kingdom is out of the asylum where the gowns apparently are made.

Stephanie Blythe, flanked by Maya Lahyani and Ying Fang: the 'steps' in full outfit and coiff...

Massenet’s score is also bipolar in this regard: Cendrillon’s music is for the most part hauntingly inward, soft, whispering, only gaining energy, hope and joy, at first through the intervention of the Fairy Godmother and then through Cendrillon’s meeting with the equally lonely Prince Charming. This mood is set in sharp contrast to the pomp, circumstance, brilliance (and volume) of the courtly music surrounding the preparation for the ball and the fallout thereafter. Though nowhere nearly as complex as in a score by Wagner, meaningful musical/vocal motifs flit through the score, as in, for instance, Cendrillon’s dreamy and longing for love and companionship, Vous êtes mon Prince Charmont, which is repeated either when she is remembering, dreaming and longing for him or when she is actually conversing with him, maybe reminding him of the crucial role he'll play in her psychological wellness. There are motifs linked with the Fairy Godmother (her vocals primarily), the oppressive step family, the pompous dandified court, etc. Wagner it’s not, nor really is the story his fach, which is probably why he didn’t write an Aschenputtel.

Alice Coote as Prince Charming and Joyce DiDonato as Cendrillon

So, as operas go, the Met’s new Cendrillon is indeed a wonderful, refined creation. Enjoy it. One suspects its deeper beauties are elusive at first exposure. All in good time.

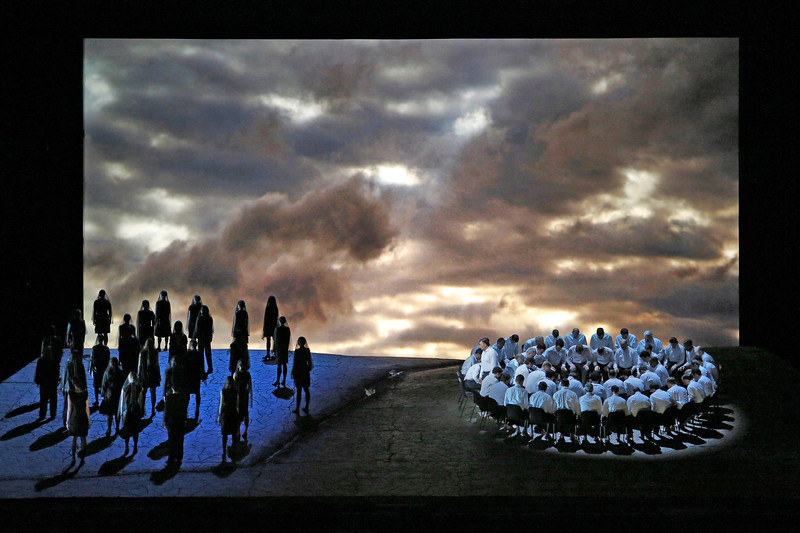

There are ample more obvious opportunities to entertain here, and, comme d’habitude, Pelly does not miss a trick: for starters, he demands a tight and constant choreographic approach to most moments in the opera, entertainingly realized by Laura Scozzi. Dancing, yes, particularly in the Ballroom Scene (Act II as written, the second scene of Act I as performed here), but more often simply as tightly coordinated movements, patterns, and synchronized gestures by collections of people (the servants, courtiers, fairies, etc.). You’ve seen the soldiers in the first Act of his La fille du régiment, oui? For contrast, compare the Met’s chorus in Luisa Miller, who basically enter, sing, then exit a scene in packs, to this: Cendrillon is in constant flux.

Joyce DiDonato as Cinderella and Laurent Naouri as her father Pandolfe

The stage itself and the props are constantly changing, such as chairs, doorways, stairways, entrances and exits. Barbara de Limburg’s unit set, sporting excerpts on the walls from the original text of the Charles Perrault’s classic (published in the collection Histoires ou contes du temps passé aka Contes de ma mère l’Oye in 1697*), is a stage wide set of high hinged panels with doorways and hiding places, augmented by separate smaller sections which can be wheeled in and out without much ado. Add an elegant gate, it becomes a ballroom at court, wheel in brick rooftops and chimneys, it’s the top of the palace, or add a door, bed and chimney, it’s Cendrillon’s dirty ragged bed. Her gentle father comes to comfort her in her misery.

The singers are first rate, totally up for the challenges. Joyce DiDonato is a sensitive Cendrillon who softly mopes and wishes for happiness, but who, along the way, runs a gamut of emotions from helplessness to a cautious ecstasy. I sure feel happy for the royal couple at the end. Laurent Naouri is her defeated, hangdog** father Pandolfe. Stephanie Blythe’s Madame de la Haltière is an outrageously funny creation, totally in her element. One wonders how she can do it without herself breaking into a fit of laughter! Blythe’s vocal range is astounding. Kathleen Kim, at the other end of the keyboard, is a high flying and silvery Fairy Godmother, also astounding.

Alice Coote, is, as written, Prince Charming, soft and lonely himself, but equally ecstatic at finding Cendrillon, who, because she’s probably frightened that the dream shall end when he learns her true identity, says, at first, Pour vous je serai l’Inconnue, unknown among all of the other dross, in spite of being oh so conspicuous in her oh so white, in contrast to everyone else’s oh so red. Ying Fang as Noémi and Maya Lahyani as Dorothée are to be praised for their coordinated movements and uncoordinated colors. Other characters scurrying about include David Leigh as the Master of Ceremonies, Petr Nekoranec as the Dean of the Faculty, Jeongcheol Cha as The Prime Minister, and Yohan Belmin as the Herald.

Betrand de Billy has been frequently associated with this score and with this production. He and the Metropolitan Orchestra create magic.

Cendrillon, in white, approaches the Prince, to stage right, as the Fairy Godmother, also in white, but well read it seems, oversees all

May the mood never end. Cendrillon is not to be missed. Enjoy!

*Apparently in the Perrault original, Lucette was dubbed “Cinderwench,” so called because her hair always had ashes in it from her sleeping on the floor by the fireside to keep warm. The younger kinder stepsister softened it to Cinderella.

**By the way, please don’t miss in the art gallery on the left wing of the main lobby William Wegman’s dogs doing Cendrillon…love those dogs! The Weimaraners. I mean, even if you’re a cat person…ya gotta love those dogs!

Reviewed performance, the Met’s 2nd: April 17, 2018.

Photos: Ken Howard.

Ciao, J.